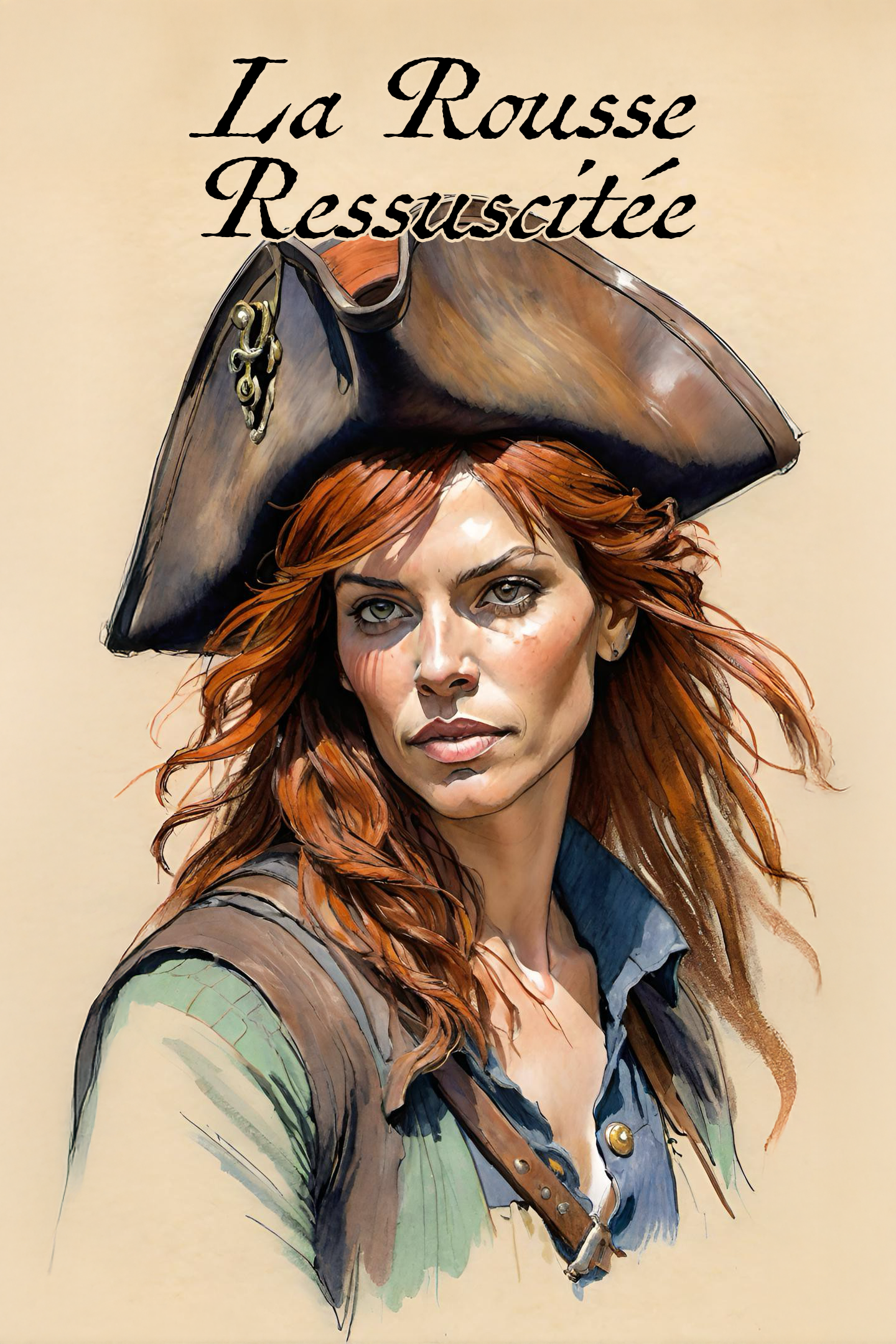

BTS: The Untrue Origin of “La Rousse Ressuscitée”

One of the characters I created for La Maupin, Mistress of the Sword never actually appears in the story. She is only seen in songs that La Maupin sings and as a role that she at times inhabits. I didn’t make her up entirely on my own. Julie insisted that we needed her, and I've borrowed from a number of other writers. Still, I think that the story of her creation is fun and not a major spoiler for the book, and so well-suited to telling here.

She is a woman without a name of her own, known merely as “La Rousse Ressuscitée”. And this is the true story of her untrue origin….

In her 1865 book “Queens of Song”, Ellen Clayton wrote:

“For some time La Maupin lived by singing in the cabarets of the towns through which she passed. She was painfully conscious of the miseries of her vagabond life, but her ambition prompted her to strive to excel, although her audience was invariably of necessity rude and ignorant. She tried to sing her very best on every occasion, and to give expression and truth as far as she could to what she sung, and adopted every means of captivating—of moving her hearers: “I tried even to compose the words and airs of some chansonnettes, which were liked well enough by my rough audiences,” she says herself.”She does not, however, tell us anything more about these little songs that la Maupin attempted—no lyrics, not even a subject. Nonetheless, since Julie spends a good deal of time on the road singing for her supper, alone or in the company of Sérannes, I was going to have to show some of her performances, and even if I didn’t include the lyrics, I would need to at least be able to describe them.

So I asked myself what the song she was singing would be about. Since in at least some instances they were accompanied by demonstrations of swordsmanship, they should include a swordswoman. That could mean a cross-dressing female soldier, but I have another use for that type of character, so… maybe a lady pirate? What of a pirate Queen? The real ones that I knew of were English or Irish, women like Anne Bonny or Mary Read. A Frenchwoman would be better. Anne Dieu-le-Veut, the wife of the Dutch pirate Laurens de Graaf might be good. Purportedly, he married her after she threatened to shoot him, which nicely presaged Julie skewering d’Albert. Unfortunately, she married de Graaf in 1693, and I needed songs for Julie to sing in the 1680s. I’d have to search a little further….

Jacquotte Delahaye

That brings us to Jacquotte Delahaye, born about two decades before Julie, and one of the few 17th century female pirates. She operated in the French Caribbean, so songs about her in French would make sense. She seemed perfect, except… she probably never really existed. There’s no contemporaneous evidence for her and it is generally agreed that French novelist Léon Treich invented her in the 1940s. That would make it a little awkward for Julie to sing about her more than 250 years earlier. But….

What if Treich made her up based on old folktales and songs? Yes, she’s fictional but based upon tropes, songs and oral traditions dating back to the 17th century. Writers seldom make things up out of whole cloth. Look at Théophile Gautier’s “Mademoiselle de Maupin”. He based her very loosely on the real La Maupin, and kept a couple of facts about her and the names of a few of the people in her life, but Mlle. de Maupin, and Madame or Mlle. Maupin are very different. Gautier wanted to tell a story of his own, but nonetheless built it on the rough skeleton of an existing person.

Who’s to say that Treich didn’t have some old source material to base his tale upon? And if he did, why can’t some of that material go back to the little songs that Julie tried her hand at, songs that may have been entertaining, but were not important enough to be be taken much notice of?

So, what do we know about Jacquotte Delahaye? Supposedly, she was born in Saint-Domingue, daughter of a Hatian woman and a French father. After being thought to have been killed, she masqueraded as a man for a while and then revealed herself. She led a sizable gang of pirates in taking over Tortuga in 1656 and eventually died defending it. British author Briony Cameron told her story in The Ballad of Jacquotte Delahaye: A Novel, one of four novels based on her life. And, of course, she gets written about in various non-fiction books and articles about badass women.

Back from the Dead Red and the naming of names

According to Treich, because of her red hair and her reappearance, she was known as “la revenue de la mort rouge”, literally something like “The Return of the Red Death”. In English, this becomes “Back from the Dead Red”, a name that seems to have taken on a life of its own. It has been used for an anime-style video, a novel that reimagines her and Calico Jack Rackham, a second indie novel—part of a short-lived series about pirates and sea monsters—a red wine from California and another from Canada, a homebrew beer recipe kit, and a death metal song.

Well, I didn’t want it to appear that I was trying to retell any of these modern stories, of either Jacquotte Delahaye or Red, so I decided to rename her and pare her story back to the bare minimum. The French phrase “la revenue de la mort rouge” is a rather odd construction, and “Back from the Dead Red” is a bit distinctive, so instead I called her “La Rousse Ressuscitée” (“The Resurrected Redhead”), though using “revenant” instead of “resurrectee” had a certain appeal.

La Rousse Ressuscitée

With that, I had the bare bones. “La Rousse Ressuscitée” would be a somewhat bawdy song of the sort sung in taverns, one that La Maupin might have heard while roistering with Gaspard, Florian and the pages. She has a remarkable memory for music and song and so can recall at least a verse or two. Its hero is a redheaded Caribbean lady pirate from a decade or three back, a perfect fit for the sort of sword and song shows that Julie and Sérannes put on during their flight to Marseille. Over time, La Maupin would add her own touches, generally in keeping with the material that Treich would eventually use to create Jacquotte.

In the past, I’ve been very fond of creating, or encountering other people’s creations of, characters who are the “reality” upon whom various fictional characters are based. For a face-to-face role playing game I once ran, I had the party encounter one Sherrinford Locksley Holmes, whose telegraph address was derived from the syllables of his first two names. He didn’t have to act like Sherlock, but only someone that could inspire his creation. In this case, La Rousse isn’t the “reality” behind Red—she’s a fiction herself, one created by Julie. As such, she’s a way for Julie to act out and to explore aspects of her personality. She is even an influence on how Julie’s personality evolves. Playing the bold pirate becomes comfortable. It helps explain who Julie is that she beats Dumésnil, threatens Thévenard, assaults her landlord and his cook. In a way, La Rousse and the more noble Chevalier de Raincy are contrasting rôles and influences on Julie. “De Raincy? Who’s that?” A story for a different time.

Bonus Snippet

Since I've walked you through her origin, it's only fair that I reveal the first appearance of La Rousse Ressuscité in the book.

For a time, their repertoire consisted of folk tunes and drinking songs she’d learned roistering with Florian and the pages. As Julie warmed to the audiences and they to her, the songs became bawdier. She would sing ditties such as “La Rousse Ressuscitée”—“The Resurrected Redhead”. It told the saucy tale of the exploits of the auburn-tressed, half-breed, pirate queen thought to have died leading the defense of the Dovecote on Tortuga, only to return, dramatically revealing that she had been passing for a man.

Julie only knew one verse of the song, but as they travelled from inn to inn, she improvised others and revised the chorus. Passing her hat while singing mock threats and wielding her sword was guaranteed to bring in several sous and occasionally the odd livre or two. Opening her tunic and teasing at the laces of her shirt as she sang of the redheaded “resurrectee’s” reveal of her womanhood was always received with howls of encouragement and not a few coins.

Soon she added a verse recounting the seduction of a rival captain, only to dash his hopes of marriage and steal his crew. At first, Sérannes played the rôle of the jilted lover, but then she started selecting one of the audience members and focusing her wiles on him. Often enough, the chosen one would contribute substantially to the passing hat.

Normally, the song would lead into the fencing demonstration between Julie and Sérannes. Once, though, as the final verse approached, Julie spotted a scalawag attempting to remove coins from the hat. She drew her sword and danced across the floor, ending with a lunge. Her tip just barely reached the rogue, pinking him. He dropped the coins back into the hat and then, as she came closer, the sword point never leaving his chest, he followed them with his own purse, to the cheers of all.